|

| A section of the ancient cave art discovered in Indonesia that depicts a type of buffalo called an anoa, at right, facing several smaller human–animal figures.Credit: Ratno Sardi |

World’s Oldest Story?

Researchers have found what they

think may be the world’s oldest recorded story. A painting discovered on the

wall of an Indonesian cave has been dated to 44,000 years old. The art appears

to show a buffalo being hunted by part-human, part-animal creatures

holding spears and possibly ropes. Details of the discovery were published in

the journal Nature by archaeologists from Griffith University in Brisbane,

Australia.

“I’ve never seen anything like

this before. I mean, we’ve seen hundreds of rock art sites in this region, but

we’ve never seen anything like a hunting scene.” says Adam Brumm, an

archaeologist at Griffith University in Brisbane.

The depiction of these animal–human figures suggest that early humans in Sulawesi had the ability to conceive of things that do not exist in the natural world, say the researchers.

|

| Drawings found in a cave called Leang Bulu'Sipong 4 in the south of Sulawesi |

The drawings were found in a cave

called Leang Bulu'Sipong 4 in the south of Sulawesi, an Indonesian island east

of Borneo. The panel, which is almost five metres wide, appears to show a type

of buffalo called an anoa, plus wild pigs found on Sulawesi. It includes

smaller figures that look human but have animal features such as tails and

snouts. The painting shows an anoa flanked by several figures holding spears

depicting a hunting scene. Some researchers, however, have questioned whether

the panel represents a single story, or a series of images painted over a

longer period.

|

| The Lion Man. Stadel Cave, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 40,000 years old. The oldest known evidence of religious belief in the world. © Ulmer Museum. |

The oldest such example from Europe is a

half-lion, half-human ivory figure from Germany that researchers have estimated

to be 40,000 years old - although some suggest that it might be significantly

younger. The Lion Man sculpture found in Stadel Cave, Baden-Württemberg,

Germany, has been described as a masterpiece. It provides the oldest known evidence

of religious belief. It stands 31 centimetres tall and has the head of a

cave lion with a partly human body.

How do we know it's 44,000 years old?

The team calculated the age of

the painting by analysing the calcite that had built up on the painting. They

found the calcite on a pig began forming at least 43,900 years ago, and the

deposits on two buffalo were at least 40,900 years old. This material builds up

in the exact same way that stalagmites and stalactites form in a cave.

The calcite incorporates small

numbers of naturally occurring radioactive uranium atoms. These atoms decay

into thorium at a very precise rate through the ages enabling researchers to

determine the age of the artwork. Scientists take a very thin films of the

deposit from just above the paint pigments. Because the film was on top, the

dates generated were minimum ages. In other words, the paintings had to be at

least as old as the calcite deposits and probably much older.

How does it compare to other prehistoric art?

However, the Indonesian drawing

is not the oldest in the world. Last year scientists reported finding what was

described as ‘humanity’s oldest drawing’ on a fragment of rock in South Africa

which was 73,000 years old.

|

| This tracing of the cave wall shows the 40,000-year-old painting on the far right. The black box shows the area which was used for dating the cave art (c) Nature |

The painting was found in a

system of caves in the remote and rugged mountains of East Kalimantan, an

Indonesian province on Borneo. The caves contain thousands of other prehistoric

paintings, drawings and other imagery, including hand stencils, animals,

abstract signs and symbols.

Co-author Maxime Aubert, from

Griffith University in Australia, commented:

"The oldest cave art

image we dated is a large painting of an unidentified animal, probably a

species of wild cattle still found in the jungles of Borneo - this has a

minimum age of around 40,000 years and is now the earliest known figurative

artwork."

The animal appears to have a

spear shaft stuck in its flank and is one of a series of similar red-orange

coloured paintings, which were made with iron-oxide pigment. These paintings,

which include other depictions of animals along with hand stencils, appear to

represent the oldest phase of art in the cave.

The researchers also dated two

red-orange hand stencils, which produced minimum ages of 37,000 years. A third

hand stencil had a maximum age of 51,800 years, even older than the animal

painting. The authors conclude that rock art locally developed in Borneo

between around 52,000 and 40,000 years ago. The older dates for cave artwork

raise the distinct possibility that these early paintings were made by our

Neanderthal cousins who shared our world with Homo Sapiens.

|

| Re-construction of Neanderthal Man |

Our distant relatives, the Neanderthals

thrived in Europe for around 300,000 years before modern humans

arrived. Excavations in Ibex, Vanguard, and Gorham’s Caves in Gibraltar

have revealed evidence of Neanderthal occupation dating to possibly as late as 28,000

years ago. Modern humans interbred not only with Neanderthals, but

also with our recently discovered relatives the Denisovans, as well as a

currently unidentified population of pre-modern hominins.

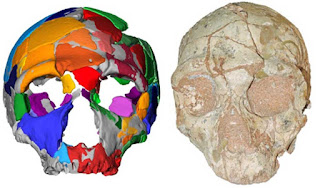

|

| Cranial features of Modern Man and Neanderthal compared |

A jawbone from a man who lived

40,000 years ago reveals that six to nine percent of his genome is Neanderthal,

the highest amount ever found in a modern human specimen. This remarkable find

indicates that a Neanderthal was in his family as close as four generations

back in his family tree - potentially his Great-Great Grandfather!

The use of symbolism - the

ability to let one thing represent another in the mind - is one of those traits

that set our animal species apart from all others. Tracing the origins of

abstract thought and behaviours, and the rate at which they developed, are

critical to understanding human development. It underpins artistic endeavour and

the use of language.

For further information see: